Panel discussion on Union Budget 2022-23

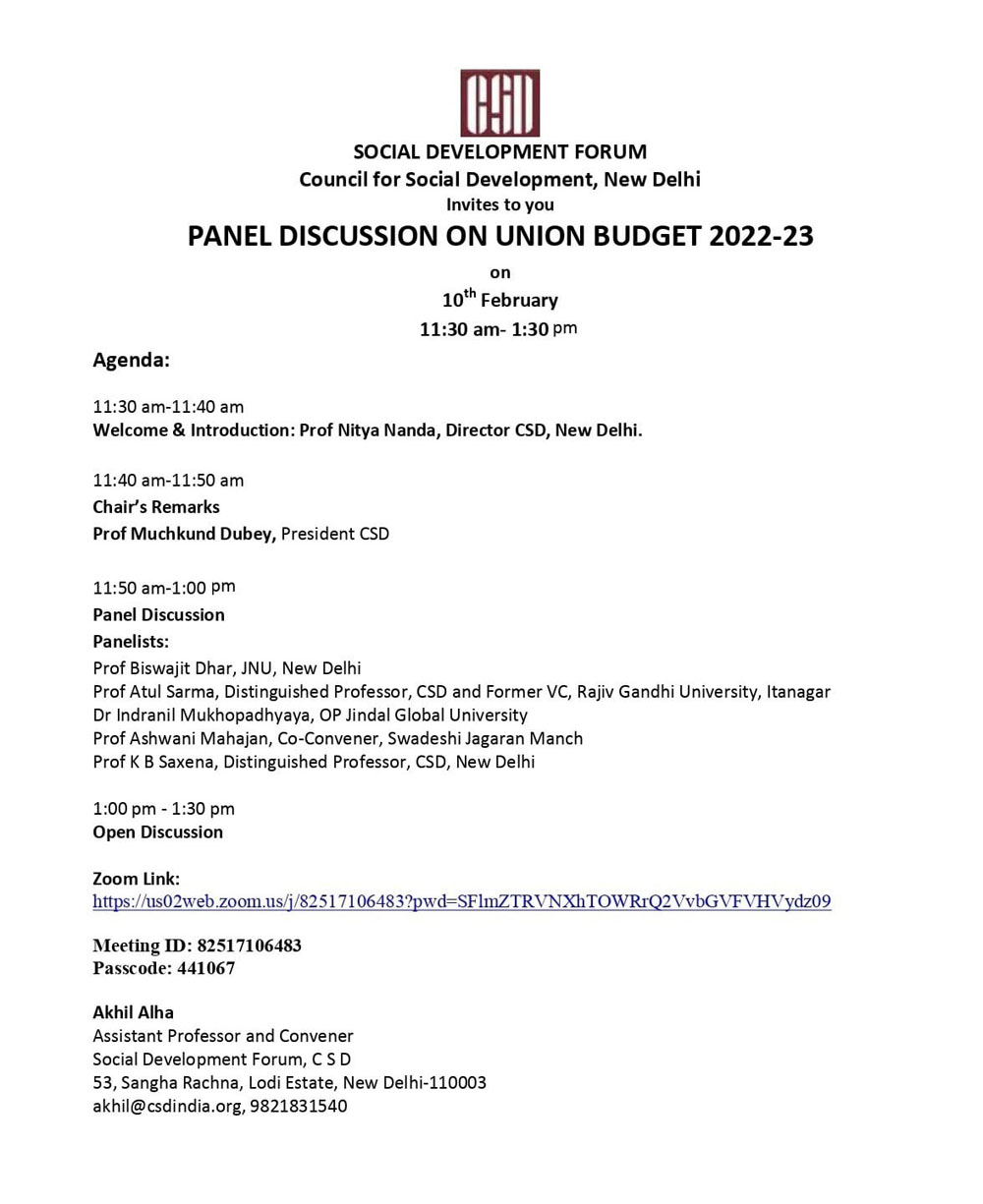

An online panel discussion on Union Budget 2022-23 was organized by the Social Development Forum of the Council for Social Development on 10 February 2022. The five panelists in the discussion were Prof Biswajit Dhar, Prof Atul Sarma, Prof Ashwani Mahajan, Prof K B Saxena and Dr Indranil Bhattacharya. Prof Nitya Nanda made the opening remarks.

The Union Budget (UB) 2022-23 has been presented at a time when the Indian economy has not fully resurrected itself from the slowdown caused by COVID-19 pandemic. The domestic consumption demand has remained subdued because of disruption in labour market while economic inequality has increased over the past two years. Hence, the union budget was expected to stimulate economic growth mainly by way of creation of employment opportunities and consumption demand in the economy.

The emphasis on infrastructure development in the union budget is a welcome step as it may provide a boost to growth and employment generation. While capital expenditure in the UB 2022-23 has increased by 24 per cent in comparison to revised estimates in 2021-22, revenue expenditure has increased by a meager 4 per cent which in real terms is in fact a decline given the current inflation rate of around 8 per cent. Low allocations for revenue expenditure and the concern of the government of keeping the fiscal deficit around 6 per cent may actually lead to shifting of allocations from the capital expenditure to revenue expenditure as the latter can neither be postponed nor reduced significantly. Besides, employment generation capacity of investment in the infrastructure sector is much lower than that in other sectors like health and education, and the gestation period in the former is also much longer.

It is important to note that 70 per cent of the fiscal deficit is going to be financed through market borrowing, through treasury bills and government securities. While the idea behind the financing of the fiscal deficit to such a great extent through market borrowing is to induce private expenditure, it may actually crowd it out.

The UB seems to have focused on sustaining economic growth in the long-term. However, long-term growth is based on three foundations: investment in the economy, infrastructure development and inclusive development. A look at the data suggests that contraction in the Indian economy that has been there even before the pandemic struck, will make the process of achieving long-term growth difficult. For instance, economic growth rate in 2019-20 came down to 3.7 per cent and the Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) came down from 34.3 per cent in 2011-12 to 28.9 per cent in 2019-20. During the same period, the rate of investment in the economy declined from 39 per cent to 32 per cent, gross savings from 35 per cent to 30.2 per cent and household savings from 23.6 per cent to 17.2 per cent. Private consumption in the economy also declined from 60.5 per cent in 2019-20 to 57.5 per cent in 2020-21. In this regard, though an increased focus on capital expenditure and expansion of infrastructure is a welcome step, the UB should have also focused on some issues of immediate concern. The first is the issue of unemployment. According to the CMIE (2020), about 23 million people lost their jobs during the pandemic. In addition to it, 11 million people join labour force every year in India. In this backdrop, the government’s commitment to create 6 million jobs in the five years period reflects that it has not fully understood the gravity of distress in India’s job market. There is not enough emphasis on the creation of employment opportunities in the union budget. If newer jobs are not created, inequality among social classes will increase further. Therefore, a thrust on employment generation in general, and small and medium scale industries in particular in the union budget was called for. This would have helped in mitigating economic inequality also.

With regard to resource mobilization, the government has maintained stability in India’s tax regime which should be welcomed. However, the Tax- GDP ratio in India, at around 18 per cent, is one of the lowest in comparison to many developing countries (where it is in the range of 22-26 per cent). Despite of there being a scope for increasing this ratio, there is no attempt towards doing so in the UB. The profit share of Bombay Stock Exchange’s top 200 companies recorded a profit of Rs. 1.6 trillion in the third quarter of 2020-21 which was higher by 57 per cent on a year-on-year comparison. In the World Inequality Report (WIR) of 2020, it is observed that the top 1 per cent of the richest Indian population owned 20.7 per cent of India’s national wealth while the bottom 50 per cent owned only 13.1 per cent. These figures have further worsened in the latest survey of WIR. According to this report, top 1 per cent in India owned 33 per cent of the country’s wealth while the bottom 50 per cent owned only 5.9 per cent. The richest 140 persons in India own a total wealth of Rs. 53 lakh crore which is much larger than the state domestic products of many Indian states. Given such a huge concentration of wealth among a few, levying a wealth tax on rich in the union budget might have enhanced resource mobilization for the government.

One of the other welcome initiatives announced in the union budget pertains to PM Gati Shakti which is a digital platform for bringing 16 Ministries including Railways and Roadways together for integrated planning and coordinated implementation of infrastructure connectivity projects. This can really help in reducing logistic cost, attract private investors, increase growth, domestic production and competitiveness of Indian industries.

The finance minister in the budget speech has also talked about protecting and promoting domestic industries which may augur well for the small and medium scale industries and generate employment.

Marginalized Sections (Women, Children, SCs and STs): The union budget has failed to address the needs of the marginalized sections in the country. Cash transfers in the Jan Dhan Yojana and free food under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyana Yojana have been stopped. Investment in public infrastructure and schemes for credit support to entrepreneurs will not have an impact on the poorest of the poor, a majority of whom fall in SC and ST categories.

With regard to women, despite the provision of gender responsive mechanism in the union budget, the government has failed to address the issues of social protection, employment and violence against women. The union budget outlay reported in the Gender Budget Statement has been increased by 11.5 per cent. But this is largely due to increased allocation for composite expenditure schemes under Part B (mainly the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY-Urban)), rather than the increased outlays for Part A schemes, which are exclusively targeted at women. There is no mention of trans-genders in the budget.

The major issue with regard to women is their low labour force participation. There has been an increase in the absolute number of women workers from 18.6 per cent in 2019-20 to 22.8 per cent in 2020-21. But this increase is largely in the family sector where no remuneration is paid. The decline in the allocation for MGNREGA will further reduce the labour force participation of women. There has already been a gap of 11 per cent in the demand and supply of wage employment in the programme. Reduction in the allocation under National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM), along with reduction in outlays towards credit support under Pradhan Manthri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) and Stand Up India will further adversely affect women. As of early 2021, women entrepreneurs had availed themselves of 68 per cent of loans under the Mudra scheme, and 81 per cent of loans under Stand-Up India. The reduced allocation for PMMY and Stand UP India will reduce the volume of loans to women entrepreneurs.

Allocation to the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP), under which Indira Gandhi National WIDOW Pension Scheme and Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme are covered, has increased by only 5 per cent over the last year.The pension amount being paid remains low and has not been revised for past many years; for instance, only Rs, 300 per month are paid to widows.

The health related issues of women have also not received adequate attention. Only 62 females per 100 males have been vaccinated against COVID-19. Several other issues such as increased incidence of anaemia, mental health issues like stress, violence etc. have not been addressed in the union budget. Several key schemes addressing violence against women such as One Stop Centre, Women Helpline, Swadhar Greh, Ujjawala and Working Women Hostel, were last year subsumed under the umbrella schemes Sambal and Samarthaya. Most of these schemes have been subjected to significant resource cuts.

Children –The total allocations for children has increased by 8 per cent in the union budget 2022-23. However, as a percentage of the total union budget, the allocations for children have shown a decline, from 2.46 per cent in 2021-22 BE to 2.35 per cent in 2022-23 BE. For Early Childhood Development (ECD), two lakh new Aanganwadi centres are to be created but no outlay for the scheme is mentioned in the union budget. Even the existing centres are underfunded, posts are lying vacant and there are non-operational centres. Allocation for child health is reduced by 6.08 percent. There has been also been a decline of 11 percent in the allocation for PM-POSHAN which was earlier called the National Programme for Mid-day Meal in schools scheme.

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes: Allocation for Post-matric scholarship for SCs has been increased by 294 per cent in the union budget but the scheme still remains under-funded due to the very low base figures, and continuous increase in the number of SC students in the post-matric classes. Allocation to Pre-matric scholarship has been reduced by 38 per cent.

The allocation for tribal development in Central Sector Schemes and Central Schemes remained only 5.5 percent of the total allocation to these schemes, which is less than the last year’s proportion. Given the extreme backwardness of this class of population, and the need to put them on equal footing with that of other sections of the population, there is a strong case for a significant increase in budgetary allocation for the welfare of STs.

Religious Minorities: While there is an increase of 4 per cent in the budget outlay for Ministry of Minority Affairs (MoMA) over the previous year’s budget, the total budget of the Ministry as a proportion of the total union budget has declined to 0.12 per cent in 2022-23 BE from 0.14 per cent in 2021-22 BE. Scholarship coverage for students from religious minority communities is very poor and the unit cost has not been revised for the past few years.

Persons with Disability: They constitute to be the most neglected sections of the Indian society. The Indira Gandhi National Disabled Pension Scheme covers only 7.6 per cent of working-age people (15-59 years). The pension amount is very low and the scheme does not cover disabled children. There is no specific programme for disabled women and girls in the gender budget. The union budget 2022-23 has offered a marginal 3 per cent increase in the allocation to the Department of Persons with Disability.

Public Health: Despite the increase in absolute terms, the share of the health budget in the total union budget has remained almost stagnant over the past few years, with 2.26 per cent of the total budgetary expenditure being earmarked for health in 2022-23 (BE). In fact, in comparison to the share in 2020-21 (RE), there has been a decline in the latest budget. There is a small increment in allocation for the crucial health schemes such as primary care, child and maternity care. Given the demand-driven nature of these schemes, allocations have to be increased at the revised estimates stage. Mental health issues have been on the rise due to pandemic, but budget allocation for the National Health Mission is inadequate and need a significant increase in allocation. The scheme’s share in total health budget has come down from 48 per cent in 2021-22 BE to 42 per cent in 2022-23 BE. NHM being the most crucial intervention for strengthening primary healthcare in the country, such a declining trend remains a cause of concern. Schemes which strengthen the health care system have been neglected in the budget. A large proportion of front line health workers are women and they get only minimal wages for their service. There is a need to increase the allocation for their welfare.

Agriculture and Rural Employment: Agricultural, the only sector which has performed steadily over the pandemic period has nothing to do with the union budget. In the UB, a few schemes for infrastructural development in the sector have been taken up along with restructuring of a few other schemes, but that will not be enough to support agriculture and huge pool of small-marginal farmers in particular.

Allocation for fertilizer subsidy has gone down in the union budget. An allocation of Rs. 2.7 lakh crore has been made for Minimum Support prices (MSP). This looks substantial in size, but 86.2 per cent of farmers in the country, who own small-marginal landholdings, may not benefit from this allocation as majority of them don’t produce enough to sell their output in the market and benefit from MSP. Allocation to MGNREGA has also declined by about 25 per cent which along with a decline in outlay for food security will result in further deterioration of the rural economy. There is no mention in the union budget of promotion of Farmers Producers Organisations (FPOs) which seem to have a huge potential of helping farmers.

School Education: Due to the conditions prevailing in the Indian school education system just before the onslaught of the corona virus Pandemic and the problems created for this system by the Pandemic, it was expected that the UB for the current financial year, the government would make a hefty increase in the allocation for school education. Before the Pandemic, most of the provisions of the RTE Act had remained unimplemented. The school infrastructure needed thoroughgoing up-gradation. Millions of teachers’ vacancies remained to be filled. An efforts was needed to be made to bring back to the school the children who dropped out of it during the Pandemic. The nation has also to make up for the very significant losses that had taken place during the corona period in the learning process of the children. All these required huge amounts of investment. During the process of pre-budget consultations the RTE Forum had made a strong plea for the enhancement of public expenditure to bring the school system in India in touch with the ground reality created by the Pandemic.

The outlay for the school education in the budget for 2022-23 belies these expectations. It is hardly calculated to solve, in ant substantial measure, any of the problems created by the Pandemic and those remained to be tackled prior to it. There has indeed been on increase in the allocation for the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, from Rs. 31050 crore in 2021-22 BE to Rs. 37383 crore in 2022-23 BE. But after taking inflation into account, this represents only a marginal increase.

A very important component of the allocation for school education is the allocation for Mid-day Meal (MDM) scheme. The allocation for it has been reduced from Rs. 11500 crore in 2021-22 BE to Rs, 10233 in 2022-23 BE. This decline in allocatin is hardly in the spirit of the new nomenclature of the scheme as Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman or P.M Poshan.

A number of highly ambitious programmes and projects for institution building in the school education sector have been included in the New Education Policy of the government. There is, however, no provision in the UB for resources against any of these projects and programmes. Let along actual provisioning, there is not even a calculation of the cost to be incurred for translating any of these projects in to reality.