Tender – Supply of Elevator

The Council for Social Development is planning to install Elevators in our office building. The Lift is to access the offices from the Ground Floor, first and second floor and also go upto the Terrace as well. We enclose the Tender document for supply of Elevator.

We are also sharing a few maps of the Lift Plan Designed by our Architect.

Kindly submit the Tender Document for supply and installation of elevator latest by August 10 , 2021.

Tender Document >>

Lift Plan >>

India needs to review its treatment of migrant labour

India needs to review its treatment of migrant labour

Manoranjan Mohanty

The root of the migrant labour crisis lay in the lack of employment opportunities in rural India, which must be restructured with vastly diversified productive activities to absorb local labour

Migrant worker stories have almost disappeared from the newspapers. Governments are preoccupied with either containing the spread of COVID-19 or re-opening the economy. Sadly, the millions of migrant labourers who were forced to head towards their homes since March 24 are still looking for support.

Some got MGNREGS jobs in their villages, but most of them are unemployed after spending time in quarantine centres. They live on paltry ration in unhygienic conditions. The fact that containing the virus and resuming production are both connected with the migrants is not sufficiently understood. Their poor living conditions and unsafe transportation made them victims of COVID-19 and its carriers, further spreading it to towns and villages which are now seeing a surge in cases.

Let us remember that migrant workers are the key element in the construction sector and industries, especially the small and medium industries. Hence, the need to appreciate a few facts and design a policy that goes beyond giving relief for a few months as charity. Migrant workers have rights as citizens, and are major drivers of the economy.

First, during the lockdown, the health emergency was as challenging as the labour faced an existential crisis due to closure of factories. This was evident in the big cities where labour from the underdeveloped states such as Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh were forced out of their premises.

Estimates on migrant labour vary, but most analysts put the figure at about 150 million, of whom about two-thirds were single migrants. If each one has about four members back at home, then the total affected would amount to another 400 million. This vast mass of humanity faced livelihood, displacement and health crisis, which is as serious as the outbreak.

Second, every agricultural labour, marginal and small farmer, small artisan, worker in a small enterprise, is a potential migrant labourer when rural economy is unable to provide a source of livelihood. The COVID-19 period brought out this phenomenon sharply. The vast majority of them were distress migrants. When many of them returned to their villages and after the quarantine period they had only MGNREGS as an employment option. Even though the government enhanced the allocation for the scheme by some Rs 40,000 crore that is not enough.

Many skilled labourers and youth declined to join that work.

The rural economy was not designed to absorb local labour. Therefore, the root of the migrant labour crisis lay in the lack of employment opportunities in rural India, which must be restructured with vastly diversified productive activities to absorb local labour. Thereafter, when they migrate it would not be out of distress, but bargaining for better prospects.

Third, it is not appreciated that the migrant labour was the main contributor to the building of urban India. The employers use them and send them off after a project is over. The few welfare measures achieved in the recent decades after long struggles do not meet their legitimate long-term needs. The charity approach was evident when three months after the lockdown, the Prime Minister announced a ‘Garib Kalyan Rozgar Yojana’ giving 125 days’ work till November.

In this situation, at least two measures are urgently required. One is to implement the existing law in letter and spirit, and ensuring this by setting up a statutory National Commission on Migrant Labour to protect the rights of migrant workers. Two, is to restructure the rural economy enabling the panchayats to plan a full-employment development programme.

Under the 1979 Act and its 2011 rules, the migrant workers are entitled to minimum wage, displacement allowance, home journey allowance, suitable accommodation facilities and medical facilities among other things. The Act warrants registration of labour contractors, employers and the enterprises where they are engaged. The state governments are obliged to conduct an audit of each establishment to ensure that the law was implemented.

The COVID-19 experience exposed how this law was only on paper and how disinterested were the labour officials to enforce it. Absence of strong migrant workers organisations made it worse. There are also neoliberal labour reforms going on restricting workers’ rights reducing all labour laws into four codes on wages, social security and welfare, industrial relations and occupational safety, health and working conditions.

On the question of making rural India an attractive, full-employment sector, one needs a change of outlook. Even China has failed in this and is facing a rural crisis. Rather than making panchayats a channel of delivery of central schemes, if they can have the power to plan for comprehensive development giving land and forest rights to the people, then distress migration will be a thing of the past.

Durgabai Deshmukh Memorial Lecture 2020

Durgabai Deshmukh Memorial Lecture 2020

DDML Webinar on

Are Today’s Crises Catastrophic Enough for Neoclassical Economists and Neoliberal Politicians to Change Their Minesets?

by Ashok Khosla

Wednesday, July 15, 2020 at 4.00 p.m.

Abstract:

Historically, deep structural change in society has originated either from charisma or from crisis. Since charismatic leaders seem to arise only once in several hundred years, for most transformative change we have to depend on crises. Indeed, the economist Milton Friedman is reputed, to have said “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste”. Although the ends for which he sought transformations were the polar opposite of what I believe is needed for a healthy and truly prosperous society, he did get the means right in an age deprived of the true mahatmas who can bring about a new societal paradigm.

The crises of today are the life-threatening products of grossly flawed intellectual and ethical choices that we have made in our search for “development” over the past few centuries — particularly during recent decades. Paradoxically though admittedly most tragically, they are also the life-saving rafts that could in principle bring us in to the safe harbour of a green, equitable and universally prosperous economy. Despite the mindsets of those who make decisions at the highest levels, with their interests so deeply vested in the status quo, it is now a matter of civilizational, human and planetary survival that we urgently and fundamentally change, and in many cases turn upside down, the assumptions and practices of both the “science” and praxis of economics.

About the Speaker

Since 1982, Chairman of the Development Alternatives Group, the world’s first social enterprise dedicated to sustainable development. Innovation by the nonprofit DA, and incubation and market delivery by the commercial affiliate, TARA create sustainable, scalable consumption and production solutions in rural India. Earlier, after faculty positions at Harvard, Ashok Khosla became Director of the Indian Government’s first Environment Office and then Director of Infoterra in UNEP. He has been Co-Chair of the UN’s International Resource Panel, President of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and President of the Club of Rome. He was a member of the Government of India’s National Security Advisory Board and Scientific Advisory Council to the Cabinet and was awarded the OBE by the UK Government, the UN’s Sasakawa Environment Prize, UAE’s Zayed International Environment Prize, WWF’s Duke of Edinburgh Medal and the Award for Outstanding Social Entrepreneur by the Schwab Foundation. He has an MA from Cambridge University and a PhD in Experimental Physics from Harvard University.

Abstracts of published papers : Dr Akhil Alha

Abstracts of published papers : Dr Akhil Alha

1. Features of the Agrarian Market in Odisha: Insights From a Field Survey

Man & Development, Vol. XLII No. 1, March 2020, ISSN 0258-0438

Abstract: This paper explores agrarian relations in Odisha and the changes occurred therein in recent years when the state’s agriculture is undergoing a pervasive agrarian crisis. On the basis of primary data collected from four villages, it finds that the volume of agricultural employment as well as long-term labour contracts are on a decline. While the structure of tenancy in partially irrigated villages has not undergone any major change in the past years, absentee landlordism as well as leasing under fixed rent in cash is on rise, while fixed produce tenancy is declining in the irrigated villages. Though non-farm opportunities generated in nearby urban areas are mostly precarious and insecure in nature, they have helped rural households in sustaining their livelihoods. These opportunities along with an improved coverage of banks and Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in extending credit have helped in loosening the bond of unfreedom in labour relations to some extent. Given the fact that the process of withdrawal of rural workforce from agriculture is very slow, the state agencies must intervene to bring agricultural sector out of the crisis through higher public investment in the form of harnessing irrigation potential available in the state, extension of credit and legitimising land leasing in the state.

2.Non-farm Diversification and Agrarian Change: The Story of a Semi- arid Village in Rajasthan

Social Change 50(2) 254–271, 2020 (June 2020 Issue)

Abstract: The paper, a study of Baspur village in Rajasthan, spans a period of five years. It argues that changes in the village economy of Baspur have been guided by a greater integration of the village with the outside world, facilitated by improved modes of communication and transport. Over the years, the increase in non-farm employment, mostly casual and informal in nature in nearby towns, has emerged as a major driver of growth and distribution of income in the village economy. This, coupled with already existing migration streams, considered essential to support livelihood, has greatly reduced the dependence of rural households on agriculture. This is evident in the reluctance of male workers towards preforming farming tasks, a decline in the incidence of land-leasing in the village and a steep rise in farm wages over the years.

Keywords Non-farm employment, tenancy, migration, occupational mobility

Land Right Movement of Dalit Women in Marathwada: Combating Poverty, Hunger and Gender Inequality

Schedule of the Programme

Speaker: Abhishek Bhosle, Assistant Professor, Vishwakarma University, Pune

Chair: Professor Manoranjan Mohanty, Distinguished Professor and Vice-President, CSD New Delhi and Editor, Social Change

Date: March 19, 2020 (Thursday)

Time: 3.00-4.30 PM

Venue: Durgabai Deshmukh Memorial Lecture Hall, CSD, Sangha Rachna, 53 Lodi Estate, New Delhi 110003

About the Presentation:

Dr B R Ambedkar on 23 February 1941 in a meeting in Solapur district gave a call to Dalits to fight for seeking government-owned wasteland for cultivation. By 1958-59 the movement spread in other parts of Maharashtra and Dalit women led the movement along with their male counterparts. Many were jailed with their kids. In 1964-65, Ambedkar’s close confidant Bhaurao alias Dadasaheb Gaikwad took the reins of the movement and launched a massive agitation of landless labourers across India to claim government land for cultivation. Over 3.4 lakh landless people were jailed across India. This was the biggest movement by Dalits in India after Dr. Ambedkar’s death in 1956. The movement came alive again in 1990 under the leadership of Eknath Awhad under the banner of Jameen Adhikar Andolan (Land Rights Movement).

As landless Dalits turned cultivators, villagers and local leaders turned furious. The struggle to get control of these wastelands and to retain cultivation rights on these lands has not been an easy one for Dalit women. They had to confront opposition not only from their families and caste mates, but also from upper castes landowners in the villages who, on experiencing labour shortage because of landless labourers turning cultivators’ often orchestrated attacks on Dalit bastis and burning standing crops on the lands cultivated by Dalits. Dalit women farmers remained undaunted by such attacks and continued cultivation as it helped them to escape severe poverty, send their children to school and gradually earn a higher say in decision making at the family and the societal level. The Maharashtra government passed orders in 1978 and then in 1991 to extend legal rights to Dalits and other backward castes who have encroached the government owned lands for cultivation. However, a majority of cultivators were left out of the legalization process because they had no proof of cultivating these lands.

This paper, based on available literature as well as personal interviews of Dalit women cultivators, traces the trajectory of Jameen Adhikar Andolan over the decades, role of women in sustaining this movement, and the mechanism through which the movement made them feel more empowered in socio-economic realm.

About the Speaker: Abhishek Bhosale, a Development Communication researcher works on the ideas of Development from the perspectives of caste and gender. His current research projects revolve around the struggle of tribals, the peasant class and landless labourers in the Shramik Movement in Shahada and Nandurbar in Maharashtra, and Dalit struggle for land rights in Marathwada. He is also actively engaged with a people’s movement at the grass root level to promote media literacy and the democratization of Media.

Abhishek is currently teaching Journalism and Mass Communication at Vishwakarma University, Pune where he is also a part of the core team for developing a research centre on Development Communication and Rural Journalism.

Abhishek has written articles and reportages on water crisis in Maharashtra and its impact on gender and caste relations, atrocities against minorities in Maharashtra, the film society movement in Kerala, and Journalism in times of conflict in Kashmir. He is a regular contributor to various media platforms like Daily Divya Marathi, Media Watch, Muktshabd, Aksharnama, Aksharlipi,etc. He also writes critical commentaries on contemporary media in the Sunday column called ‘Media Mania’ for Dainik Divya Marathi. He is on the review committee of a bilingual communication journal called ‘Media Messenger’.

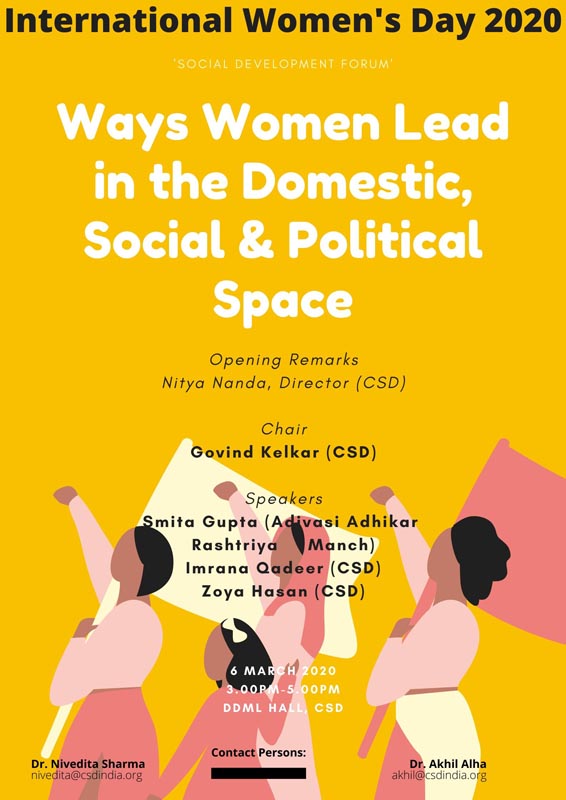

International Women’s Day 2020 – Ways Women Lead in the Domestic, Social & Political Space

Schedule of the Programme

Welcome and Opening Remarks

Dr. Nitya Nanda

Director, CSD New Delhi

Speakers

- Ms. Smita Gupta

Adivasi Adhikar Rashtriya Manch - Prof. Imrana Qadeer

Council for Social Development, New Delhi - Prof. Zoya Hasan

Council for Social Development, New Delhi

Chair

Prof Govind Kelkar

Council for Social Development, New Delhi

Date: March 6, 2020 (Friday)

Time: 3:00-5:00 PM

Venue: Durgabai Deshmukh Memorial Lecture Hall, CSD, Sangha Rachna, 53 Lodi Estate, New Delhi 110003

We sincerely hope that you will join and enrich the panel discussion.

Dr Nivedita Sharma Dr Akhil Alha

(nivedita@csdindia.org) (akhil@csdindia.org)

“I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress women have achieved”

-Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

Gender-based issues have had a long standing history in the academic, social and policy circles world-wide. The issues are multiple, highly varied, complex and multi-layered. Inquiries into these issues reveal deep-rooted inequalities, explicit as well as implicit, that have fostered discrimination across space and time with negative consequences on the overall development and well-being of women.

In the domestic sphere, women of the household not only have fewer resources but also face disproportionate burden of unpaid house-work. All these inequalities are both a cause and effect of low status of women in the house and their minimal participation in the decision-making process. Further, patterns of social hierarchies, dominance of patriarchal systems and cultural and religious norms have fostered a society where women have been denied the right to make strategic choices/decisions about their lives; to go out and work, to access education & skill-development, to access productive resources, to access healthcare etc. Also, class and caste based discrimination further add to the vulnerabilities of the women.

Another important aspect of overall well-being is availability of adequate exposure to political life. Even in the era of highly-representative governments, the role of women in public life is substantially limited, in most developed nations as well. Lack of political participation by women exists both in terms of active involvement as representatives and also as a group to be represented. Women’s ability to organize themselves in social groups, self-help groups or other groups for mutual benefits including religious and community- based organizations reflects the magnitude of liberality among citizens of the society in accepting women in public life. Access to political decision-making has long-term consequences for the equitable development of the society.

Earlier there was an overall lack of consciousness and understanding about the structures of patriarchy functioning within families, homes and society at large. Women were indeed ignored. But this very ignorance generated a counter-intuitive process of delving deep into individual experiences, and unpacking patriarchy through them. It gave birth to new perspectives, a feminist consciousness, reflections on the productive and reproductive roles of women, their practical and strategic needs, the impact of patriarchy on women’s individual and collective lives and their abilities to cope, counter, and resolve. There is thus increased awareness level of women in the domestic, social and political space and the participation of women is evolving in reclaiming their rights.

It is in this context that Social Development Forum of Council for Social Development, New Delhi would like to observe International Women’s Day with a panel discussion on

Training Workshop on Social Impact Assessment and Resettlement Planning

Date : 25th – 27th February, 2020

Venue: India International Centre, New Delhi

The programme this year was focused on ‘Social Impact Assessment and Resettlement Planning’. The objective of this workshop is to familiarize participants with newer, more effective ways of managing the emerging resettlement challenges. The workshop will be suitable for senior/middle level government officials, public sector personnel, industry managers, NGOs, academics, trainers and also those working in international development agencies as well as personnel working on projects financed by them.

Council for Social Development, New Delhi invites you to a panel discussion on Union Budget 2020-21

Date: 18 February 2020

Venue: DDM Hall, Council for Social Development, 53, Sangha Rachna, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi-110003

Programme Details

Session I: Macroeconomic Aspects of Union Budget 2020-21 (10.00-11.30 AM)

Chair: Professor Muchkund Dubey

Panelists:

- Prof Biswajit Dhar, JNU

- Prof Abhijit Das, Head, Centre for WTO studies, IIFT

- Prof Atul Sarma, CSD

- Prof Nitya Nanda, CSD

Tea: 11.30-11.45 AM

Session II: Social Sector Schemes and Marginalised Sections in Union Budget (11.45 AM-1.15 PM)

Chair: Prof K B Saxena, CSD

Panelists:

- Prof Muchkund Dubey, CSD

- Prof Ritupriya Mehrotra, CSMCH, JNU

- Prof R Govinda, CSD

Lunch: 1.15-2.00 PM

Session III: Agricultural and Rural Development in Union Budget (2:00-3.30 PM)

Chair: Prof Praveen Jha, JNU

Panelists:

- Prof T Haque, CSD

- Dr Ashwini Majahan, Swadeshi Jagaran Manch and PGDAV College, DU

- Prof Ashok Pankaj, CSD

Ambedkar’s Theory of the Social: The Universal Condition of Recognition

Speaker: Prof Martin Fuchs, University of Erfurt, Germany and German Co-Director, ICAS: MP

Chair: Professor K B Saxena, Distinguished Professor, CSD New Delhi

Date: February 13, 2020 (Thursday)

Time: 3.00-4.30 PM

Venue: Durgabai Deshmukh Memorial Lecture Hall, CSD, Sangha Rachna, 53 Lodi Estate, New Delhi 110003

About the Talk: Social Justice as understood by Babasaheb Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar can be taken as a shorthand for a whole bundle of values and norms which a decent society is meant to provide and which is required for each of its members to be able to lead a dignified life. While Ambedkar put strong emphasis on the chance for each individual to develop his or her capabilities, equality and justice for him had to be grounded on mutual respect, social recognition and compassion, or what he, with others, called fellow-feeling.

Ambedkar’s attempt to achieve this in the case of his own society through political struggle and by legal means – culminating in his work on the Indian Constitution – was accompanied by his endeavour to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of society and explore the

role of social values therein. He both explored the place and possibilities of social ethics and thought of ways of establishing such ethics that would generate a just society. It was in this context that the question of religion achieved special prominence for Ambedkar.

The presentation reconstructs Ambedkar’s sociological and socio-philosophical explorations of the conditions for a just society. The focus is on what one could call Ambedkar’s theory of the social, which underlies his conceptualization of religion and of social and religious change. The talk starts by looking at Ambedkar’s emphasis on social values and on the dispositional and attitudinal dimensions of social behaviour that affect the ways people relate to each other. This is followed by a discussion of his views of the social significance of religion and his attempts to distinguish between religion that realizes the human core values, and religion that fails on the criterion of justice. The overall argument refers to the ontological assumptions regarding human nature and the nature of human sociality underlying Ambedkar’s views.

About the Author: Martin Fuchs studied Anthropology, Sociology und Modern South Asian Languages and Literatures at the Universities Marburg, Heidelberg and Frankfurt/Main, and received his PhD from the University Frankfurt/Main. This was followed by teaching appointments at the Universities of Zürich, Heidelberg and the Free University in Berlin. At the Free University he also did his Habilitation (postdoctoral qualification).

In the following years Martin Fuchs held teaching and research positions at the Universities of Paderborn; Heidelberg (South Asia Institute); Free University Berlin; Central European University, Budapest; and the University of Canterbury, Christchurch (New Zealand). Martin Fuchs was Founding Director of the New Zealand South Asia Centre (2008-2009). Since 2009 Martin Fuchs holds the Professorship of Indian Religious History at the Max Weber Centre for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies (Max-Weber-Kolleg) of the University of Erfurt.

The research interests of Martin Fuchs lie in Cultural and Social Theory; the Anthropology, Sociology and Religious Studies of South Asia; Social and religious movements; Dalit studies; Urban Anthropology and Human Rights issues.